Our opinion is that our sailboat is the perfect liveaboard bug-out sailboat... for us.

And that's really the main point, this is what we consider perfect. You may look at our choices and go with the exact opposite. So there may be no perfect boat for everyone, but here's the choices we made and why.

Part 1 contains:

- Motorboat or Sailboat

- Monohull or Multihull

- Hull Length

- Saildrive versus Direct Drive

- Fixed, Folding & Feathering. Choosing the Right Propeller

- Diesel Engines or Electric Motors

- Electrical Power

- Water

- Masts & Sails

- Anchors

- Engine Location

- Galley

- Tenders (dinghies)

- AIS

- Hull material. Wood, steel, aluminum or plastic

Motorboat or Sailboat

Without a question, motorboats are faster. But they require fuel. You have a choice of gasoline or diesel. Never choose gasoline on a boat! Gasoline is explosive, and very dangerous. Diesel is a very safe fuel, and will give you more miles as well.

Today, fuel is expensive. Tomorrow, it may not be available.

There will always be wind, and it's free.

Monohull or Multihull

This argument has been raging for years, and likely will be for many more. Our primary reasons for choosing a multihull are:

- Faster sailing. Other than into the wind, multihulls are faster than monohulls. This means you can cover more miles each day, and you can outrun storms better.

- Less draft. With two (or three) hulls you do not need a large keel sticking deep in the water to stay right side up. This means we can go places that a monohull can't go.

- More comfort. Sailing flat is much more comfortable than sailing heeled over.

- Safety. Multihulls, because they do not have several tons of ballast, are lighter than water. That means if you should punch a hole and fill with water, you will still float. I have seen catamarans that have sat bouncing on a reef for a week. Looking into the hulls there was no floor, you looked straight down into the ocean. But they still floated.

For these reasons we went with a catamaran. You can read more about the benefits of multihulls at this link.

Hull Length

Usually price and your money will determine the size of your boat. But if you are lucky enough to be able to afford anything, then you have to select the size that is right for you.

Boats will always be smaller than a house on land. But the bigger boat has many benefits over smaller vessels.

- Longer boats are faster than shorter boats. Due to the way waves form from the bow, a boat will have a hull speed that is very difficult to exceed. The longer the boats waterline (Length at WaterLine = LWL) the faster that hull speed is.

- The larger the interior, the more space there is. This means more private cabins, more living space, and more separation from each occupant. Remember, this is not a weekend away where everyone can sleep in the living room. When living aboard you will want the same things you look for in a house. Private rooms away from the noise of the living area, a decent kitchen, and at least two heads (toilets).

- Larger, heavier boats, behave better in rough water than smaller lighter boats.

So you may think, "I will just get a 50 meter boat". The drawbacks to larger boats are:

- Cost. Both the cost to purchase as well as the cost to maintain increases exponentially. Double the size is likely to cost four times the amount.

- Complexity. Larger boats need larger pieces of equipment, and more of it. Maintaining some of this equipment gets very complicated.

- Crew. The larger the vessel, the more crew you will need. And that means more space is needed, and more food, and more crew to look after the crew... it's a never ending cycle.

You should be able to handle your vessel, under most conditions, by yourself.

For us, there is myself (57M) and my wife (52F). That means that I should be able to sail the boat by myself in nearly all condition. Should I be incapacitated, my wife must be able to sail the vessel to the nearest help.

This limits the size of the vessel to about 15 meters (50 feet). It is possible, with electric winches, and power assist devices for a single person to handle a boat that is more than 15m, but it is not advisable. If you should lose power and have to do everything manually, you need to be able to do it.

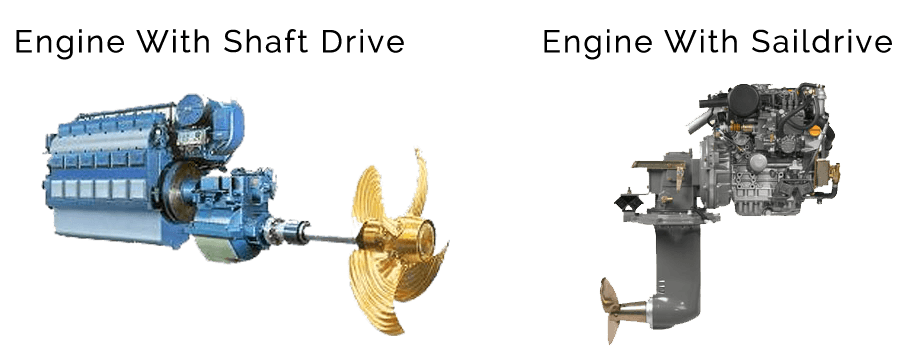

Saildrive versus Direct Drive

A sail drive allows the engine to be placed further aft, while still having the propeller in front of the rudder.

While they have a lot of benefits, they have several drawbacks in a bug-out boat.

- They can only be serviced by pulling the boat out of the water.

- From what I have been told (and I may be mistaken) they are lubricated when the engine powers them. This means when the engine is off, there is no lubrication, which is why you are told to put them in gear to prevent the propeller from free-spinning.

- The casing for saildrives is usually made from aluminum. Should you have a stray current in your boat, or not enough zincs, this could result in corrosion of the saildrive housing and failure of the unit. A 5 to 8 centimeter stainless steel drive shaft would need a great deal of corrosion before it failed.

Since we were replacing our engines with electric motors (we'll get to that below) we needed to be able to have the water turn our propellers, and that then turn the motors. Without lubrication, this would not be good.

We opted for a boat that had a direct drive (also called a shaft drive). This means the engine turns the propeller shaft, and that shaft goes out through the hull.

With a direct drive, all serviceable parts are located inside the hull. This means you can perform maintenance and repairs with the boat still in the water.

It also means that with the correct propeller installed, we can generate electricity while sailing.

Fixed, Folding & Feathering. Choosing the Right Propeller

Fixed bladed propellers are simple, and inexpensive. As long as you get the correct size, then you can't go wrong.

Fixed bladed propellers are simple, and inexpensive. As long as you get the correct size, then you can't go wrong.

Folding propellers are a little more complicated, and must be kept clean to work. Barnacles in the gears can prevent them from opening and closing properly. When there is no power to them, the moving water causes the blades to fold back, allowing for less drag. When under power the centrifugal force on the blades causes them to spring outwards, allowing the propeller to work.

The most expensive, and most complicated, is the feathering propeller. This type of propeller comes in two forms, automatic and adjustable. When strictly under sail, the blades would be aligned to the boat, and act like knife blades slicing through the water with no drag. When under power, they would be rotated to act like propeller blades.

An automatic feathering propeller works similar to a folding propeller, in that the drive shaft rotating causes them to turn into position. The adjustable feathering propeller has a control rod that causes the blades to rotate to the desired position.

We opted for the adjustable feathering propeller. This gave us the best bite when under power (similar to a fixed prop), and zero drag when under sail. Since we have electric motors, these propellers allow us to slowly rotate the blades so that the water moving passed them spins the drive shaft. This turns the electric motors, which then function as electric generators.

Line Cutters

Before we finish with propellers, this is a good time to mention line cutters. In a normal live-aboard, putting line cutters on your propellers is a nice insurance policy. They are easier to fit them at your next haul-out than having to dive to clear a fouled prop. In a post-disaster scenario, they can mean the difference between life and death.

One thing to keep in mind is that fouling may not be accidental. In fact, we carry lines on each stern intentionally ready to throw overboard to foul the propeller of anyone chasing us.

Diesel Engines or Electric Motors

Diesel Engines

There is a lot to be said in favour of diesel engines. They are usually strong, reliable, and long-lasting. They are fairly simple machines, and tend to run well. Diesel fuel is very energy dense. Kilogram to kilogram, there is little better storage of energy than diesel fuel.

The drawbacks are the price of the fuel, and for a bug-out boat, the availability of fuel. If things turn bad, finding fuel may be very difficult.

There are two other things to consider in a bug-out boat with diesel fuel.

First is the noise. While relatively quiet above the surface, the sound does travel and can be heard for some distance. Underwater, the sound travels a great distance.

Second is the smell. Diesel exhaust smell can travel, and alert people to your presence.

Both of these could alert a person to your presence, and anyone watching would certainly see that you have started your engines.

Diesel engines work best at one speed. Unlike a car engine that has a wide range of speed, diesels work best when under load at their optimal RPM. Going slower wastes fuel and causes the engine to get dirty, while going faster causes excessive fuel usage and wear.

Fuel Polisher

While on the subject of diesel engines, this is a good time to mention fuel polishers. Diesel engines are very reliable, but one thing that will stop them dead is dirty fuel.

Fuel polishing equipment effectively removes various contaminants from the fuel. At it's most basic, a fuel polisher is a very fine fuel filter, with a pump to move the fuel. Not only does it remove solids, but water as well. They will usually be set up with a series of valves and hoses connected to all your fuel tanks. This allows you to draw fuel from any tank, filter it, and direct the output to another tank.

Having a fuel polisher is very important, especially if you will be purchasing fuel from some out-of-the-way locations where there may be water or other contaminents in the fuel.

Electric Motors

Electric motors are silent, both above the surface and below.

They produce zero exhaust, and so no smell.

They can go from off to full speed in a second, with out the need to "start" the engine.

The drawback is that at current time, battery storage is limited, thereby greatly limiting the range.

With the right propeller, they can generate electricity while you are under sail. We have managed to generate over 6kw from our two motors.

Hybrid

We opted for a hybrid solution.

When we purchased our catamaran it was equipped with a pair of 60 hp diesel engines. There was also two gensets. I forget their exact size but I think there was a 6kw and a 15kw.

We pulled out the two diesel drive engines and installed two 20kw electric drive motors.

We installed a 29kwh battery bank consisting of 8 x SimpliPhi LiFePO4 48v 75Ah batteries. This allows us to travel about 30 nautical miles at 9.4 knots. At reduced speed we can travel considerably further. If the sun is shining on our solar panels, that could extend indefinitely.

We pulled out the two gensets and installed a pair of 20 kW Polar Power diesel DC generators. These units always run at the optimal speed for their engine, so always get the best power and fuel conservation. With 800 liters of diesel fuel onboard, we can travel in excess of 1,000 nautical miles (or run our air conditioners for a month).

Of course, when the wind blows we don't need the motors.

We have a computer controlled charging system onboard. To make certain that our batteries are not damaged, when they drop below 20% (about 5kwh) one of the diesel generators will automatically kick in to bring the batteries up to 80% (about 1 hour). The final charge from 80 to 100% comes from the solar panels. The charging system program can be over-ridden to allow us to charge, or not, as we choose. We could allow the batteries to drain to 0% (never do that!), or we could allow the generators to charge the batteries to 100%. The default settings are simply that, default. It's what the boat will do on it's own without any intervention.

Electrical Power

Solar Panels

Solar panels are cheap, and getting cheaper. They are silent, with no noise or vibration. They are completely reliable with very little that can break or go wrong. They work best in direct sun, but also work in partial sun, or even with light overcast. If you have the space for them, add them. Then find more space, and add more.

Wind Turbine

Depending upon where you will be travelling, wind turbines may be beneficial. I have found them to be expensive, and not very efficient. Even in the Caribbean where there's "always" 15 knots of wind, I found minimal output from our wind generator. Dollar for dollar, the solar panels will give you more power than a wind gen. Now, if you've run out of space for more solar panels, then a wind gen may be your only option.

Water Turbine

If you have electric motors, then you should absolutely opt for hydro-generation.

Without electric motors, you still have options of adding a hydro-generator on a drop-down leg.

If you have diesel engines with a direct drive, then I have also seen electric generators installed with a belt drive from the drive shaft. The generator would be smaller, but it may be a good alternative to going without.

Of course, hydro generators only work while you are sailing, and not while at anchor.

Our Solution

On our boat we put in 4 arrays of solar panels, with three 380 watt panels in each array. Each array has it's own charge controller. Our twelve panels give us a total of 4560 watts. This means we could go from empty batteries to full batteries in one day.

As previously mentioned, our electric motors can be hydro generators while under sail.

While sailing a good breeze on sunny days, we have been able to go from our safe minimum (20% charge) to 100% full in under 3 hours.

Water

You're not going to be very happy without water. Besides needing it to drink, you will find that a good source of fresh water really does make a huge difference in your level of comfort.

It is possible to shower in salt water, with a final fresh water rinse. Likewise, you can wash dishes with salt water and do a final fresh water rinse. If you simply do not have enough fresh water, you may not have a choice.

But you should plan on having plenty of fresh water. It is better to have too much, than too little. You should have at least 15 to 20 liters per day for each person.

The simplest and least expensive is simply adding a rain catcher to your boat. In the Caribbean there is usually plenty of rain. Let the first few minutes of rain rinse off your rain catcher to remove dust and salt, then catch the remaining.

We have a 25 m² rain catcher built into our cockpit cover. It produces 250 L per cm of rain. That enough for a family of four for four days.

If you have the money, a watermaker is essential. They are expensive, but in my opinion, worth every dollar.

Watermakers

There is a wide range of options for watermakers. You can get units that are 12 volt, 120 (or 240) volt, gas powered, or units that run off your diesel drive engine.

DC Electric (12 volt)

Usually producing less water per hour than other types, they have the benefit of being able to run from your batteries, thereby running 24 hours a day.

One drawback from some of these units is the noise. Due to 12 volt motors not being very powerful, these tend to work like piston pumps to increase the pressure. This can cause a “ker-thunk, ker-thunk, ker-thunk” noise pattern. When installed on an interior bulkhead, the bulkhead can become a soundboard to amplify the noise. If you are purchasing a boat with a 12 volt unit installed, turn it on and lay quietly in every bed to see if it is tolerable. Remember, that a mild disturbance on the day you are looking at a boat, will turn into a major annoyance when it’s nonstop night and day.

There are 12 volt DC units that do not use a piston pump, and can be very quiet. They tend to be the most expensive option. A good unit, with proper installation, can be nearly silent.

AC Electric (120/240 volt)

Units running off what is typically called “mains electric” can produce copious volumes in a relatively short period. With a strong battery bank and inverter, they can be very effective.

These units are usually the quietest, and least expensive.

Gas powered

There are units that have their own gas engine to run the high pressure pump. Like the AC powered units they can produce a lot of water in a relatively short timeframe.

The downsides are that they are noisier than electric units, and you must have gasoline on board. Gas engines should never be run inside the boat, meaning you have to carry the unit outside to run it.

If gasoline becomes expensive, or scarce, it could seriously affect your ability to create water.

Drive Engine

These units run off the drive belt of your diesel propulsion engines. Since they are powered by the drive belt, they can not produce as much water as units with their own gas engine, or AC powered units.

Additionally, you have to run your engine for a few hours to produce water. On the other hand, if you run your engines every few days anyway, then this unit is giving you “free” water.

Since the unit does not have it’s own engine, it is lighter than the other types.

If diesel becomes expensive, or scarce, it could seriously affect your ability to create water.

Our Solution

We installed a 12 volt Spectra Ventura 200c watermaker. It silently produces up to 750 L per day. That would be enough water for 40 to 50 people. That means that in the future, we have the ability to sell (or trade) fresh drinking water.

Currently, we only run the watermaker for a short time each day when the battery bank approaches full charge. As mentioned above, it's automated to come on as the batteries reach 95% if the sun is shining or we're sailing and generating electricity.

Our water is stored in 6 x 250 liter poly tanks under salon floor. This gives us 1500 liters of fresh water, or 75 to 100 person-days.